When Loss Became Language

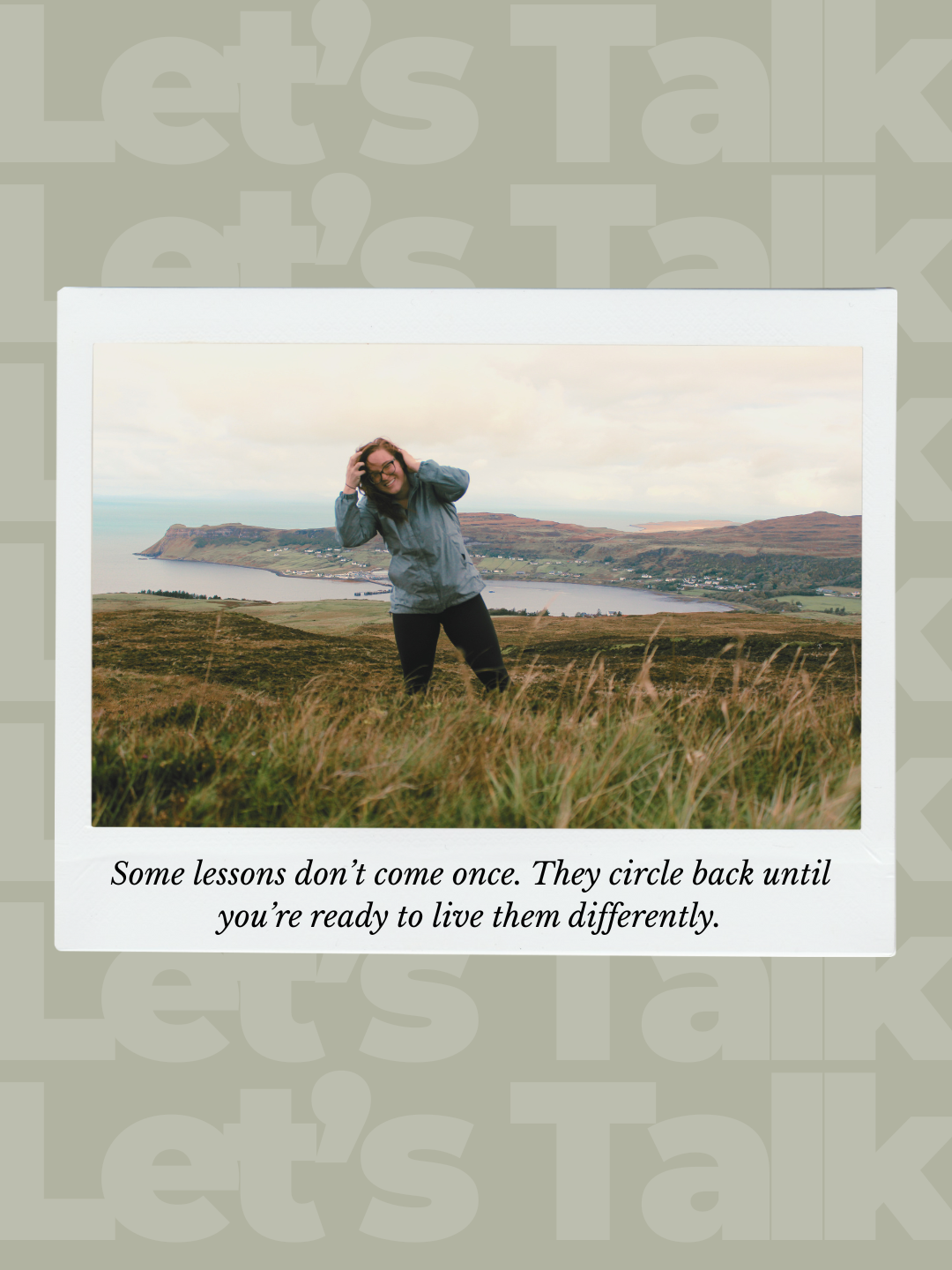

Some lessons don’t come once. They circle back until you’re ready to live them differently.

My foot sank knee-deep into the bog before I even realized what had happened. The ground gave way beneath me — cold, spongy, alive — and in one clumsy motion, I was on my chest, palms pressed into wet moss, clawing at the earth to pull myself free. I managed to save my shoe. My phone wasn’t so lucky.

It slipped quietly, almost politely, into the dark water. Gone.

I stood there for a moment, mud dripping from my hands, heart pounding against the silence. “This is the problem,” I thought. “This is what’s wrong.”

I spent the next half hour trudging through the bog, retracing steps, clawing through moss and dead plant matter, convinced that if I just looked hard enough, I could undo the loss. But the earth had swallowed it whole.

When I finally gave up and looked around, the world felt impossibly wide. The gray sky hung low over Loch Snizort, the water glinting against the green hills. A view so stunning I wanted to reach for my phone to capture it, to prove I’d been here. But all I could do was stand there, hands empty.

It’s been eight years, and that phone is probably somewhere out in the Atlantic by now. But what I really lost that day wasn’t my phone.

Before the Bog — From Surrounded to Solitary

For days, I walked the Isle of Skye with a strange mix of freedom and loneliness. Without my phone, there was no one to text, no social media to scroll, no noise to hide behind. I thought I’d feel present — enlightened, even — but instead I just felt... exposed.

Uig (ooo-ig) is small, tiny, really—a population of 423. The post office doubles as the convenience store, and the only road in town curls toward the sea like it, too, is trying to leave. Most travelers pass through just long enough to see the Fairy Glen or catch the ferry to the Outer Hebrides. It was the most remote place I’d ever been — still ever been.

A stark contrast to Edinburgh, where I’d spent the last three weeks working at the Fringe Festival. There, I was surrounded by noise and people—a constant current of conversation, performance, and possibility. Someone was always asking if I wanted to grab a pint or see a show. The city felt alive, pulsing with attention.

In Uig, everything was hushed. My mornings were spent cleaning toilets and changing bed linens at the hostel, while my afternoons were spent hiking through the rolling green hills. By evening, I’d make dinner and curl up by the window overlooking the bay with a book in hand. The kind of silence that once sounded like peace now felt like an echo.

I told myself I came here to slow down — to see all that Scotland had to offer, to prove I could be content in my own company. But I think I was running from something, too. I wanted a change of scenery, but not necessarily the solitude that came with it.

My phone was my tether, a lifeline back to the world. I could be alone, but I wasn’t alone-alone. Every text, every scroll, every post was proof that I still existed somewhere, to someone. It kept me from having to sit in the silence and ask the harder questions — about what I was doing there, and what I was really looking for.

I didn’t know it yet, but that tiny device had been keeping me afloat. When it slipped beneath the bog water, so did my illusion of control.

From the constant companionship of Edinburgh to the loneliness of Skye.

The Immediate Aftermath — Reactive Mode

As I clawed through the bog, praying for the faint ping of Find My iPhone, I already knew it was gone. There would be no miracle alert, no vibration beneath the peat—just silence. And for the first time since landing in Skye, I couldn’t outrun it.

I wasn’t just cut off from the Internet; I was cut off from everyone who tethered me to myself. The new friends I’d made at the Fringe. My parents back in the States. My brother in Germany. My best friend, who was about to get married, a wedding I would now only imagine through memory, not photos.

When I cleaned hostel rooms for four hours a day, there were no playlists, no podcasts—just the rhythm of the mop against tile and the occasional hostel guest outside. As the tourist season ended, fewer guests came through. The nights grew darker, longer. I didn’t have a car, and without a phone to check bus times, I often had to flag one down or hitchhike into the next town.

Afternoons used to be for hiking — long trails that carved through hills and ended in views that made the loneliness worth it. But without a phone, I couldn’t risk wandering too far. I didn’t know if the trail markers were reliable, and there was no one to call if I got lost. So I stayed closer to the hostel, circling familiar paths until they became both comforting and claustrophobic.

But the silence was consuming.

I became frantic, replaying the loss as if I could will the phone back into my hands. I told anyone who’d listen, “I lost my phone,” pretending that was the whole story. But what I was really grieving was the life I’d begun to build—the friends I’d made, the version of myself who finally felt at home. The phone was something I could name; the rest was harder: the quiet unravelling of a dream I wasn’t ready to leave behind.

When the reality finally sank in — that the phone wasn’t coming back — I had two choices. Keep spiraling, or doing something. So I started writing. I spent my evenings furiously typing on my computer while I watched the last boat come into the harbor. I was writing to help make sense of all that was unravelling around me, all the shoulds that were closing in, all the what-ifs and uncertainties.

The Unraveling — When the Silence Got Loud

Actually, that’s how Going With Renée began — the earliest version of what would become reneemichaela.com. It was a Squarespace domain purchased on a rainy, drab day when I had nothing to lose and everything to gain. I wasn’t sure where I was going — and I didn’t know it then — but losing that phone became the first tiny crack in my shell, the one that let the light in.

And once the light found its way through, I couldn’t distract myself from it anymore.

I had to sit with the disappointment of leaving the life I’d built in Scotland — the slow realization that I couldn’t make my dream of living there a reality.

I had to face the shoulds:

you should get a real job,

you should be farther along by now,

you have a master’s degree — shouldn’t you know what’s next?

So I scrambled. I applied for visas to stay in the UK, and when those doors closed, I applied for jobs back in the States. Each rejection felt heavier than the last. I’d stare out the hostel window at the fog rolling over the Trotternish Ridge, feeling like that same fog had settled over my future.

I thought I was reacting to the loss of a phone.

But really, I was reacting to the loss of control.

So I wrote — poorly, awkwardly, fumbling my way through the ache. I didn’t know what I was doing; I just knew it helped me breathe. Putting words on a page kept me grounded when everything else felt like it was falling into the bog.

Eight years later, when everything fell apart again, the same pattern returned. In April 2025, I lost my job — and without thinking, I did exactly what I did in that hostel.

I panicked. I applied. I tried to fix it. And then, I wrote.

I reopened my blog and began breathing life back into it, the same way I was trying to breathe life back into myself. It became my anchor again. A place to pour the overwhelm, to understand the burnout that had quietly swallowed my joy, and to trace the shape of the discontent I’d been avoiding.

Eight years apart, and I can see it now — the parallel paths.

Both times, I thought I’d lost everything.

Both times, writing showed me I hadn’t.

But there was a middle chapter, too — a city that nearly broke me before it brought me back.

The Slow Recognition — The Phone Was Never the Point

Boston, 2019.

Three years after the bog, and I was still chasing control. I’d landed what I thought was my “dream” job — the kind you’re supposed to want when you have a master’s degree, a title, and an apartment in a shiny neighborhood. On paper, it was progress. In practice, it was slow erosion.

My commute ballooned from forty minutes and one bus to ninety minutes and three, all so my boss could get a better rent deal. My role shifted from marketing to PR, which meant sending the same templated email 150 times a day. I was miserable. I had panic attacks on the bus, grateful the ride was long enough to pull myself together before work.

When my boss called me in for a “review” and said my footsteps were too loud for her empathic personality, something in me snapped.

By the time I quit, I was burned out, disillusioned, and terrified of what it meant to start over again. Another failed plan. Another “wrong” city. So, I did what I’ve always done when the ground disappears beneath me — I wrote.

That month after I quit, I filled notebooks the way I would soon fill my suitcases to move again. I wrote about the ache of disappointment, the people I missed, the guilt of wanting something different, and the strange quiet that follows when you’re unsure of what comes next.

Then I packed a literal bag and spent a month wandering through Europe — alone, again — scribbling in cafés, on trains, in hostel bunks. I didn’t realize it then, but I was repeating the same ritual I began on the Isle of Skye: turning loss into language.

Now, at thirty-two, I can finally see the pattern. Every time I’ve lost something that defined me — a phone, a job, a version of who I thought I should be — I’ve written my way back to myself.

Back then, I called it coping. Now, I call it returning.

Because maybe that was the lesson all along: writing isn’t what I do when life falls apart, it’s what shows me how to live through the becoming.

I’ve written many chapters, but there are still many more to come.

If you got this far, consider subscribing via Substack.

You can get my weekly essays right to your inbox (and they include a personal note from me).

Perfectionism doesn't make you better—it just keeps you stuck. Here's how the 80% rule helped me overcome my creative block and start creating after 10 years of waiting to be "ready."